Last month we introduced our first profile in a monthly series on the important role of science journalists to global development and sustainable impact work.

We were excited to spotlight in October journalist Rodrigo Pérez Ortega, whose contributions include not only compelling features like the one we included in our spotlight on the boom in fossil amber research in Myanmar, but also fostering much needed inclusion of foreign science journalists in the spectrum of science-based bylines.

Pérez Ortega is currently a staff writer at Science magazine, focusing on diversity in science, and editorial director of The Open Notebook en Español. Immediately following our published Insights, Pérez Ortega was one of two bestowed with the National Academies’ inaugural Eric and Wendy Schmidt Awards for Excellence in Science Communication.

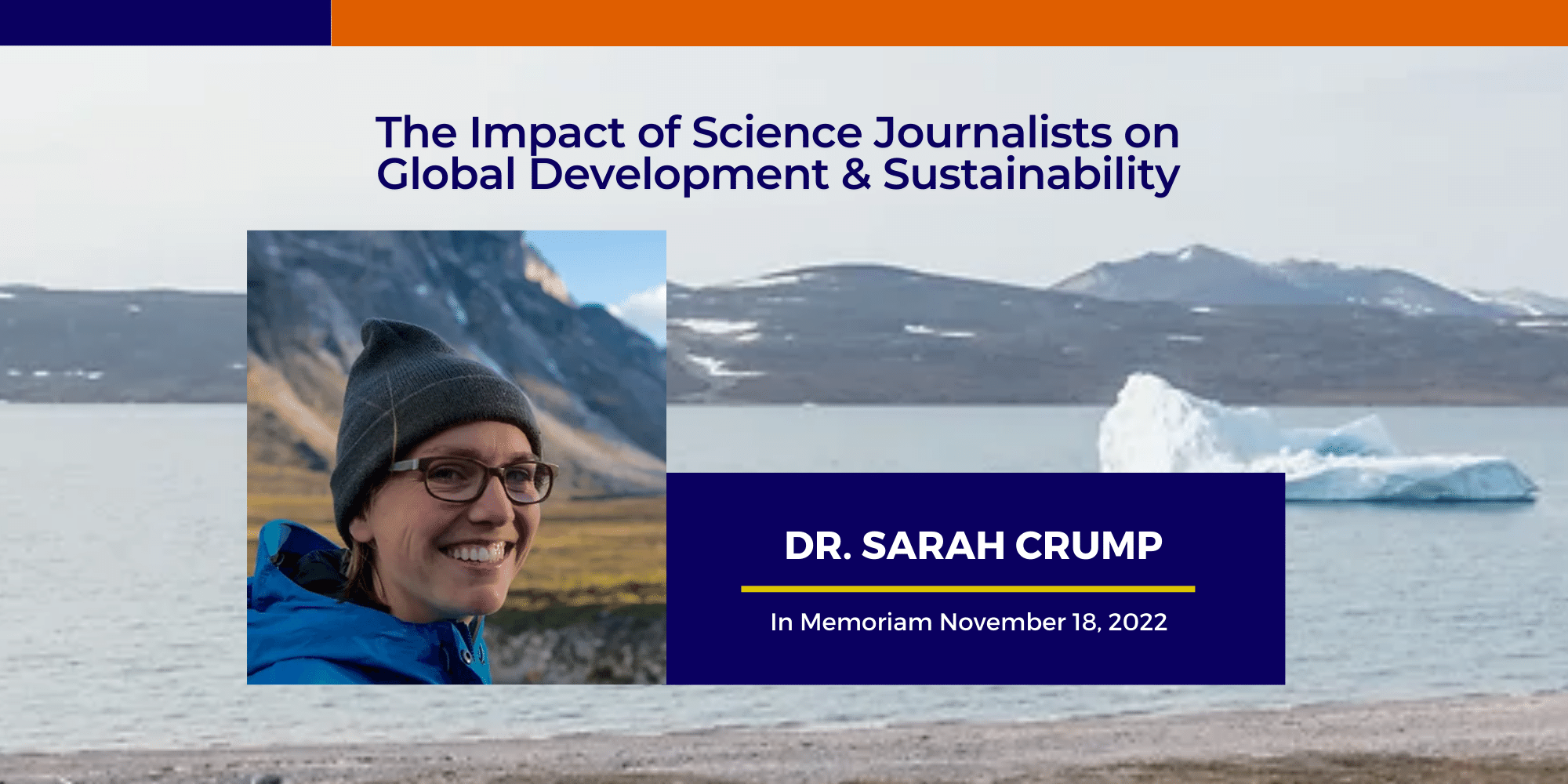

This month, we honor in memoriam the critical work of researcher, professor, and science writer Dr. Sarah Crump, who died peacefully on November 18, 2022 after a brief battle with a rare and aggressive form of cancer.

As a paleoclimate scientist, Dr. Crump studied past climate change in Arctic and alpine settings to better understand how our environment might change as Earth warms in the coming decades.

Here we touch on Crump’s 2018 contribution to Scientific American in which she writes about her expedition with field partner Greg de Wet to study lake sediments on Baffin Island, a rugged land mass just west of Greenland. At the time, Dr. Crump was a post-doc at the Institute of Arctic and Alpine Research and Department of Geological Sciences, University of Colorado Boulder.

How “Old, Cold Mud” Can Tell the Story of a Changing Climate

As we are learning, while the whole earth is warming, Artic temperatures are skyrocketing. In fact, the Arctic is expected to warm nearly twice as much as the rest of the planet by the end of this century.

Paleoclimatologists like Crump are not surprised by this. In their study of climate change through the lens of Earth’s history, data indicates temperature swings in the Arctic have always been more dramatic than those at lower latitudes. Crump and other scientists like her attempt to predict what changes and impacts might be expected in the Arctic by better understanding how Arctic ecosystems have responded to periods of past warming.

One of the critical roles of science journalists is to bridge scientific topics and research in such a way it becomes accessible to general lay audiences. In the SA article, Crump writes about her research trek to Baffin Island to collect sediment samples from a small lake called CF8 like she has ripped pages from her personal expedition journal.

From the rafts she purchased from Amazon (are they “workable enough?”) to the team’s encounters with polar bears, Crump takes her readers on a journey to better understand what goes into sampling (and what might, at any time, go wrong), and why research like this is so important.

As Crump writes, the mud that accumulates at the bottom of the lake serves as an archive of past environmental change, indirectly documenting changes in temperature and ecology continuously over thousands of years.

“Paleoclimatologists have spent decades honing the analytical tools we use to read and interpret such archives, and methods continue to evolve,” she notes in introducing her team’s new approach at the time of her study.

Her methods include extracting ancient plant DNA from the mud to reconstruct a series of time-stamped snapshots of the plant communities that lived around the lake through time. She explains how the frigid Arctic waters act as a refrigerator, keeping DNA preserved for tens of thousands of years.

Crump’s expedition, which also included local Inuk guide Lasalie Joanasie, and photographer Zach Montes, successfully procured three 5-foot-long sediment cores from the lake before moving on to other coring locations to collect samples that would allow comparisons among ancient plant communities in contrasting settings.

These locations were also on a veritable polar bear thoroughfare, which provided not only real-life challenges to the team, but added suspense and grandeur to Crump’s reporting.

The team also published a multi-media film of their trek, also embedded in the SA article (online) linked through her website:

In a mere 3+ minutes, Dr. Crump and her team convey through immersive story the techniques and methods used to study intermittent changes over time to predict what might happen to the landscape as the earth continues to warm.

What did Crump’s Team Learn About the Artic Via Sedimentary DNA?

Upon their return, Crump’s research team at the University of Boulder headed to the lab with their core samples, presenting their preliminary results in 2019 at the annual meeting of the American Geophysical Union. An article in Science written by earth and planetary science reporter Paul Voosen picked up where the SA article left off in its detailing of Crump’s coring expedition to explain the process of extracting DNA from samples for further analysis.

According to Voosen, the mud samples collected from Baffin Island did harbor ancient DNA of vegetation from as far back as the emian, a period 125,000 years ago when the Arctic was warmer than today. Dr. Crump anticipated her team’s findings would make significant contributions on two fronts.

- First, their work opens a window on the ecosystems that flourished in the high Arctic at a time when the temperatures were a few degrees warmer than today (perhaps where we are headed with continued warming).

- Second, the findings attest to the power of sedimentary DNA as a record of how Arctic plants responded to past climate shifts and may offer insights at how they might respond in the future.

Ulrike Herzschuh, a paleoecologist at the Alfred Wegener Institute in Potsdam, Germany, who also uses the technique to study how the larch forests of Siberia in Russia reacted after the end of the last ice age nearly 12,000 years ago, noted in the article, “We are now at the point that this is a really useful signal for reconstructing biodiversity.”

With the costs of genetic sequencing declining substantially, core collecting in the Artic tundra has boomed in recent years given how the cold temperatures contribute to the preservation of DNA in everything from lake and cave soils, the permafrost, and even molecular clues to the giant ice age animals that roamed there alongside very different vegetation.

What Can We Learn from the Work of Science Researcher-Journalists Like Dr. Crump?

Dr. Crump’s work holds clue for our future world in a changing climate. As part of a team, her academic publishing record from this research expedition alone is extensive (see below for links) and has made an important contribution to better understanding not only the potential of sedimentary DNA as a methodological approach, but in better understanding the dynamism of biodiversity in the Artic region.

Often researchers concentrate on academic publishing, and if we are lucky, stellar science journalists translate this body of work for the public. Sometimes, as is the case with Dr. Crump, researchers are journalistically visionary, looking for ways at the onset of a research project to plan for and develop communication and education opportunities that make scientific methods, principles, and findings, more accessible to others.

She wrote of the importance of science communication,

“Communicating research outside of the academic realm and engaging the broader public in geoscience is key to making our work more effective and relevant. My recent communication efforts include visual art, a video project, and science writing through the NPR SciCommers program. Participating in workshops like ComSciCon and the WiSE SciComm Symposium have not only helped me hone my jargon-free communication skills—they've made me a better scientist.”

Dr. Crump and many researchers serve critical roles as science journalists, using not only the written word, but multimedia, exhibits, and GIS-based storymaps to convey findings and the research journey.

Through the work of Dr. Crump and others like her, researchers as science journalists help us construct a record of ecosystems past to better help us predict the future and potential impacts and changes. This is a challenging, but critical contribution that can aid global development initiatives, partnership design, and sustainable impact work, particularly in the context of addressing wicked problems like climate change.

Dr. Crump’s Legacy to Continue through Fellowship at UC Boulder

Dr. Sarah Crump lost her brief battle to a rare cancer on November 18, 2022, just as her research contributions and academic career were accelerating. Her work has already had a tremendous impact.

Two days prior, she announced to her many followers of her blog and social media accounts the newly established Sarah Crump Graduate Fellowship Fund at the University of Colorado, Boulder’s Institute of Arctic and Alpine Research (INSTAAR).

With an aim of raising $1.5 million, the fund is designed to help support a full-year Graduate Research Fellowship providing salary and tuition for one INSTAAR grad student each year. The intent is to give a boost to their study of Earth or environmental science in Arctic or alpine regions, and to be a lever for equity and underserved communities.

To learn more about this Fellowship, how you can contribute, and the life and work of Dr. Sarah Crump, you may visit this link at INSTAAR.

To learn more about Dr. Crump’s work, visit her website.

In addition to the Scientific American and Science articles reported here, Dr. Sarah Crump’s contributions to academic publishing are extensive. Here is a list of her many lead and co-authored publications. Learn more and link to her articles via her academic profile on Google Scholar.