Those who have contributed the least to climate change are often the most affected by its current and future impacts. This is certainly the case in the Philippines, where a robust USAID-funded program seeks to reduce threats not to only fragile fisheries and marine ecosystems, but also to the coastal communities dependent on seafood production for food and livelihoods security.

The USAID/Fish Right Program (2018-2025) aims to address biodiversity threats, improve marine ecosystem governance, and increase fish biomass in selected marine key biodiversity areas in the Philippines. As a sub-implementer, Resonance led the public-private partnerships (PPP) strategy and initiatives to support coastal and marine biodiversity conservation and an ecosystem approach to fisheries management (EAFM).

With any well-meaning conservation initiative, there may be a missing economic or behavioral change that is needed to catalyze and sustain desired outcomes. USAID’s publication “The Nature of Conservation Enterprises” highlights an interdependence between secure livelihoods and incomes of natural resource users (in this case, small-scale fishers) and their ability to participate in decision-making and compliance on harvest controls and other management measures.

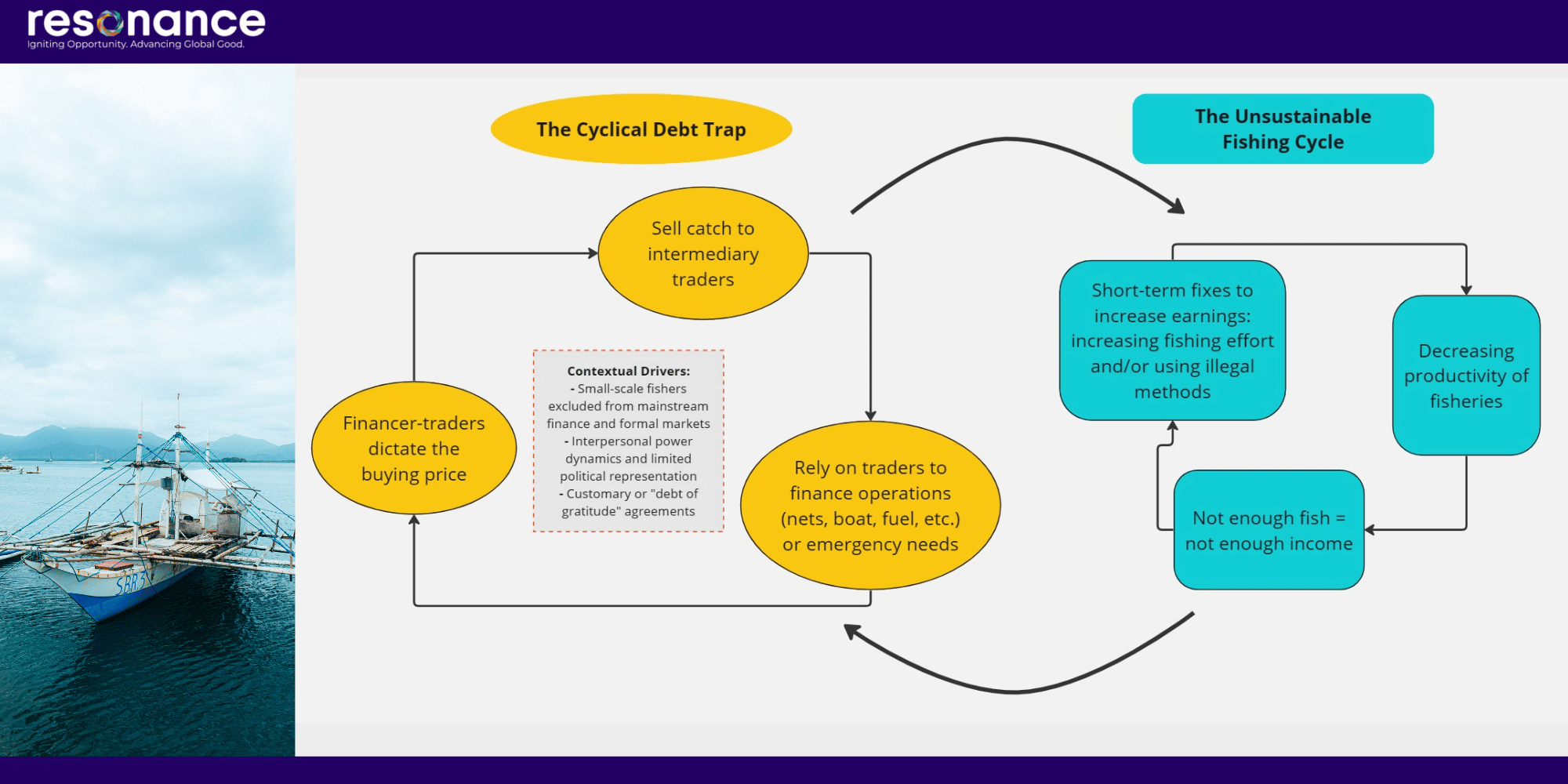

In the Philippines, many fishers live near or below the national poverty line and are relegated to the informal market. With limited access to mainstream finance or commercial buyers, fishers can fall into debt traps with the intermediaries who bring their catch to market and dictate their own terms. In parallel, open access and non-compliance with harvest control measures have greatly reduced the productivity of most fisheries in the Philippines, making it more and more difficult to catch enough fish to meet income needs. The graphic below illustrates this multi-layered vicious cycle of financial insecurity and unsustainable short-term fixes that threaten the long-term health of fisheries.

From early in Fish Right’s implementation, the People’s Organizations (POs) of fisherfolk that we engaged had ubiquitously identified improved livelihoods as key to sustainable fisheries management and expressed a clear need for alternative and/or supplementary income sources if they were to comply with sustainability-driven measures that could restrict their meager livelihoods. Human well-being and equity needed to be at the core of our partnership efforts.

Human Well-being Approach

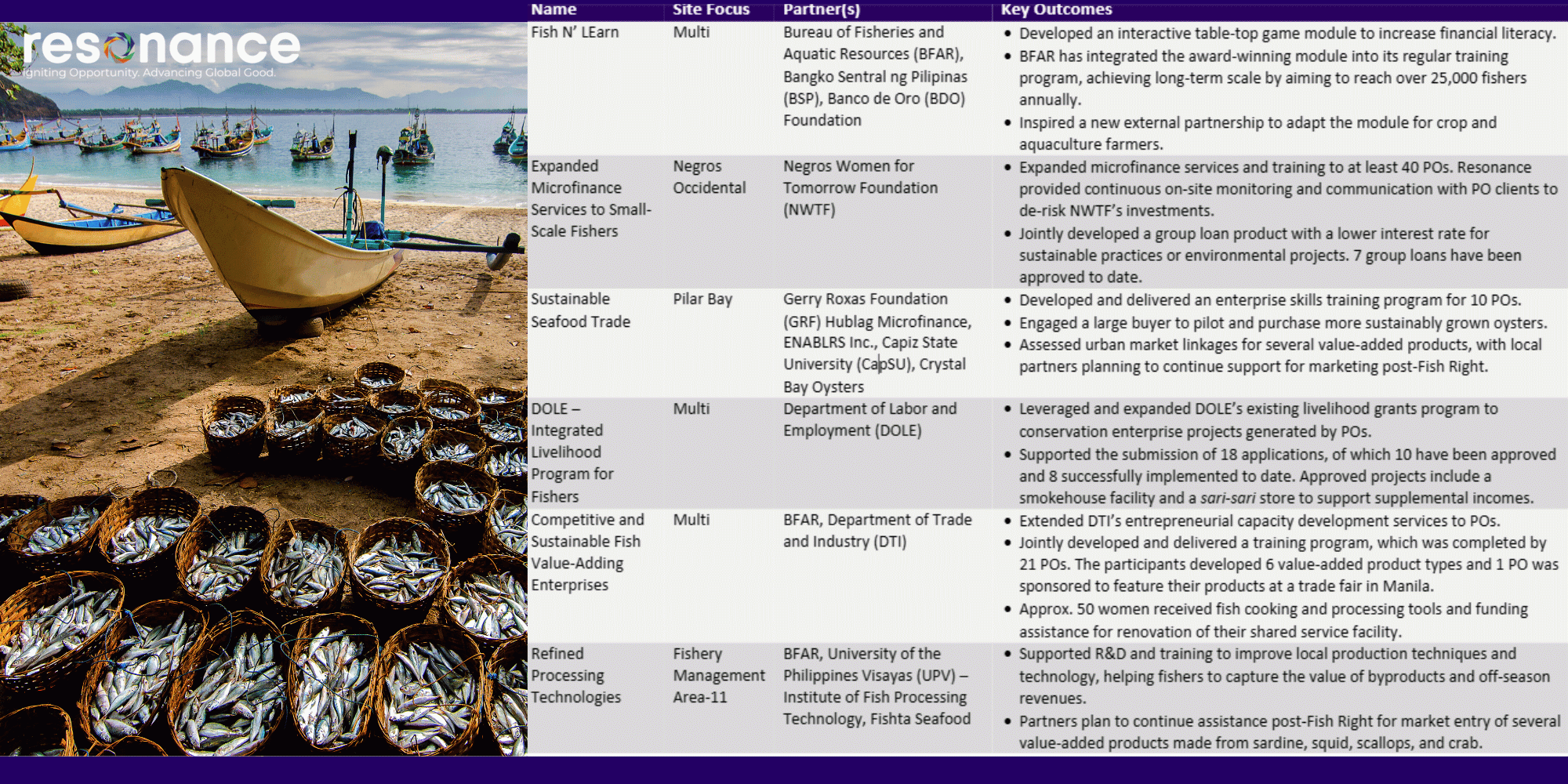

Over Fish Right’s first five years, Resonance developed 12 PPPs to mobilize participation and investment in biodiversity conservation and EAFM. Some of these partnerships were intended to improve safety nets and livelihoods as a socio-economic complement to the program’s governance and ecological interventions.

For example, by reducing post-harvest losses and leveraging value-adding processes, fishers could generate more income from the same fish catch. Building enterprise capacity, along with the backing of Fish Right and local partners, could also prepare them to engage with larger financial and/or commercial actors..png?width=2000&height=1000&name=Communities%20of%20Practice%20(14).png)

Beginning in Fish Right’s third year, and amid the COVID-19 pandemic, Resonance focused on developing conservation enterprises through targeted POs to ensure inclusive gains from EAFM acceleration. We anchored this approach on creating positive feedback loops between fisherfolks’ knowledge and stewardship of local coastal resources and the scalability of group interventions for sustainable incomes.

Resonance facilitated timely PPPs with government agencies tasked with improving livelihoods and standards for market competitiveness, as well as microfinance providers, NGOs, universities, and seafood buyers. These partnerships, in unique configurations per intervention site, provided fishers with three mutually reinforcing elements for sustainable livelihoods:

- Trainings and services on the technical and entrepreneurial aspects of conservation enterprise operations.

- Grant and loan financing opportunities through microfinance providers, provincial government offices, and on-site NGO partners.

- Direct market linkages for organized fishers’ groups to expand options for selling their catch or products, and have more information on market prices, ultimately leading to more equitable participation in value chains.

This produced six complementary safety nets PPPs, summarized below.

Under the scope and mandate of Fish Right, PPPs proved to be a key tool to address lynchpin socio-economic drivers for fisheries management improvements. But when we work on “wicked problems” such as the long-term health of our natural environment, there isn’t just one gap or one simple solution. Often, we think about partnerships individually, or several partnerships operating independently but in support of a common project or donor objective.

A project of this duration and complexity benefited from the ability to nurture scale across partnerships, not just within one partnership. As development practitioners increasingly turn to multi-stakeholder collaboration to address complex or wicked problems, a best practice would be to seize opportunities for shared value and learning between seemingly separate partnership efforts.

Synergy and Sustainability

Resonance took an innovative approach to identify and leverage synergy between these safety nets PPPs over the project life. POs were able to access training from partners like the University of the Philippines Visayas (UPV), Capiz State University (CapSU) and several banking and microfinance institutions, which prepared them to receive financing or equipment from government partners such as the Departments of Labor and Employment (DOLE) and Trade and Industry (DTI) and microfinance partners, and then to access big-name buyers like Fishta Seafood and Crystal Bay Oysters. The same fishing communities could identify increasing economic benefits from multiple interlocking interventions.

In many cases, Resonance facilitated introductions between public and private sector organizations that had not worked closely together previously or had not focused on fishers in the past—including DTI, DOLE, Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas (BSP), and Banco de Oro (BDO) Foundation. We facilitated joint assessments to increase understanding of the context for specific sites and POs, as well as the value that each stakeholder could potentially bring to and gain from collaboration on these issues. As one example, DTI acknowledged the challenges facing fishers’ groups, which were not its traditional clients, and became a committed partner.

Resonance utilized co-design to build trust, diffuse risks, and stretch stakeholders beyond their traditional roles or resourcing constraints. The support of site-specific NGOs, local government units, and the Bureau of Fisheries and Aquatic Resources (BFAR) provincial fishery offices gave confidence for enterprise support agencies, such as DTI and DOLE, to be more flexible on the requirements of their services and allow piloting of joint interventions. By capitalizing on existing capacities and initiatives on the ground, including under-utilized facilities and resources, small tweaks could generate big changes. Leveraging and sharing of resources were also evident in the development of joint training programs to ensure aligned content and adequate staffing to address the needs of participating POs.

Resonance also included deliberate efforts to promote upscaling and internal transformations among partners to continue activities and explore additional avenues of cooperation post-Fish Right.

Creating and maintaining partnerships with organizations that are not solely focused on the fisheries sector, but can cater to fishers’ socio-economic needs, may appear to strain limited time and resources. However, doing so could unlock financial and technical resources to incentivize the compliance and cooperation needed to advance responsible fishing practices and bring fishing effort to a sustainable level. Unconventional partners may help to remove barriers or fill gaps in the ecosystem—and in turn discover organizational alignment and incentives to support issues or communities that they hadn’t considered before.

Global Reflections

Environmental and economic problems—and solutions—are inextricably linked. Communities in areas of both high poverty and high ecological significance, where livelihoods are highly dependent on these at-risk natural resources, are often the focus of donor programming and environmental organizations. If conservation-focused interventions are expected to achieve sustainable results, implementing organizations must take care to include and uplift the humans within that ecosystem, particularly those who have been historically marginalized.

This dilemma is not unique to “developing” countries either. We see livelihood challenges echoed across calls for environmental justice and just transitions, such as the tax and jobs policies laid out in US legislative efforts like the Inflation Reduction Act and the Green New Deal. Amid big-picture talk of decarbonization, people are rightfully concerned about the loss of livelihoods for coal mining communities, or the short-term costs and risks for farmers to roll out regenerative practices. By leveraging innovative economic initiatives, we can make sure vulnerable groups are not left behind in fighting climate change but instead will benefit from the vast opportunities that are possible with emerging green industries, practices, and technologies.