The World Economic Forum's annual meeting in Switzerland - more commonly known as Davos - takes place each January, with business and world leaders gathering this year for discussions on the 2023 theme of "Cooperation in a Fragmented World.”

In theory and hoped practice, Davos deliberations bring together leaders of government, business, and civil society thought to possess the knowledge, expertise, and clout to facilitate positive influence at a time of unprecedented challenge and breakpoint change.

Heading into Davos 2023 there was much anticipation regarding the participants and the agenda, particularly coming on the heels of COP27 and a resolution to support a fund for loss and damage, and the UN Conference on Biodiversity (COP15) that concluded with a landmark agreement to protect 30 per cent of the planet’s lands, coastal areas and inland waters by the end of the decade.

Most forecasting articles and previews of the leadership meeting recognize our challenges sit at this very nexus of climate change and the seeming collapse of our ecosystems, or what many are dubbing a probable mass extinction event. Today’s leaders, and society at large, are facing the greatest collection action problem of our time.

In fact, according to participants who have taken to social media and reporters hitting their evening deadlines, Day 1 at Davos focused on a dominant and emerging theme related to this problem: the reality of a [potential] looming global 'Polycrisis.'

What is a Polycrisis?

Essentially when present and future risks start to interact with each other, a polycrisis can form. This cluster of global risks with compounding effects can result in the overall cumulative impact exceeding the sum of each individual risk.

In their technical paper for the Cascade Institute, authors Dr. Michael Lawrence, Dr. Scott Janzwood, and Dr. Thomas Homer-Dixon suggest a polycrisis occurs “when crises in multiple global systems become entangled in ways that significantly degrade humanity’s prospects.”

In a polycrisis, the extent of interconnectedness of systems can transcend geographic boundaries and beyond events or snapshots in time. The dense interconnectivity of these systems, according to the authors, enables a relatively small problem in one part of the system to spread rapidly and disable the entire system.

The concept is not new, but it has been dubbed by many as one of the most used buzzwords in the last two years (COVID has been used effectively to illustrate the integrative nature of a polycrisis).

The term was thought to have been first and briefly introduced in the mainstream in the book Homeland Earth: A Manifesto for a New Millennium authored by theorist Edgar Morin and co-author Brigitte Kern (1999). The authors wrote of “interwoven and overlapping crises” affecting humanity and argued that the most “vital” problem of the day was not any single threat but the “complex intersolidarity of problems, antagonisms, crises, uncontrollable processes, and the general crisis of the planet”—a phenomenon they labeled the polycrisis (Morin and Kern 1999, 74).

Since then, this concept has been used with nuanced distinctiveness – with some describing systemic challenges across the social, economic, and environmental as simultaneous, interlocking, and nested (Swilling, 2019), producing interactions that multiply the collective crises’ total impact. Others use the term more narrowly, to describe ‘financial stressors’ during certain regions or timeframes that might lead to financial collapse, ‘societal stressors (e.g., poverty or war), or ‘technological stressors’ such as cyber threats, automation, or AI.

The diversity in use of the term reinforces the Cascade authors’ contention that of our understanding of this systemic phenomenon, “Several institutions concerned with global risk have highlighted such connections as a critical gap in our knowledge that requires urgent attention.”

It is also important to note, they caution, that we often frame some of society’s most pressing challenges through the framing of risk, be it ‘systemic risk,’ ‘catastrophic risk,’ or ‘existential risk.’ However, they note these established concepts “do not adequately highlight these crisis interactions, even though they do capture essential aspects of the phenomenon.”

Davos Preceded by Global Risks Report

Many were not surprised that the first day of Davos would be framed around the urgency of addressing a looming polycrisis. The talks were preceded by the World Economic Forum’s (WEF) published Global Risks Report 2023, the culmination of a large annual survey of 1,200 experts across the WEF’s diverse network in collaboration with Marsh McLennan and Zurich Insurance Group.

In the Preface to the report, Saadia Zahidi, WEF Managing Director, writes, “In recognition of growing complexity and uncertainty [of the many challenges], the report also explores connections between these risks. The analysis focuses on a potential "polycrisis", relating to shortages in natural resources such as food, water, and metals and minerals, illustrating the associated socioeconomic and environmental fall-out through a set of potential futures.”

The report contends existing challenges are being amplified by comparatively new developments in the global risks landscape, including “unsustainable levels of debt, a new era of low growth, low global investment and de-globalization, a decline in human development after decades of progress, rapid and unconstrained development of dual-use (civilian and military) technologies, and the growing pressure of climate change impacts and ambitions in an evershrinking window for transition to a 1.5°C world."

Together, these are converging to shape a unique, uncertain, and turbulent decade to come.

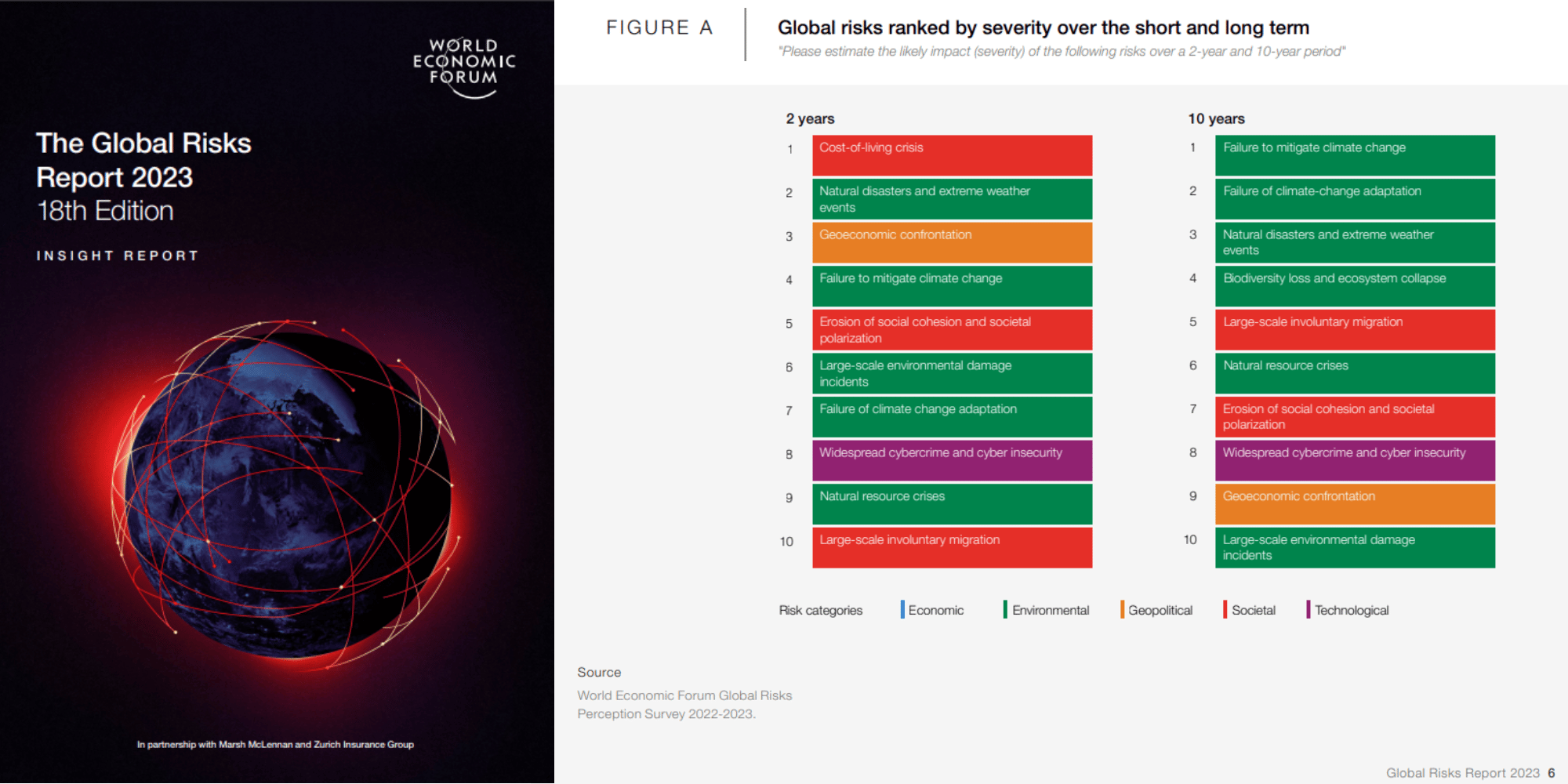

Respondents were asked to estimate the likely impact (severity) of identified global risks over the next 2-year and 1—year period, depicted in the following figure included in the report.

Notably, mitigation of climate change factors, biodiversity loss, and mass migration (linked to both) are thought to be the most severe global risks we will face in the next decade, highlighting the multiple areas where the world is at a critical inflection point.

Notes Zahidi, “It is a call to action, to collectively prepare for the next crisis the world may face and, in doing so, shape a pathway to a more stable, resilient world.”

If We are Facing a Looming Polycrisis, What Next?

Whether simply cliché as some leaders have suggested, or less bleak in tone than initially framed considering we may be dodging a global recission, the notion of a looming polycrisis may simply be too nebulous and too complex to effectively address at Davos, particularly with several world leaders absent. As a result, the term might dissipate by the end of the forum as merely a buzzword rather than a real conceptualization of intersecting global risks worth further examination and elaboration.

Regardless, the cascading crises we are facing today have many characteristics of wicked problems on their own; interlocking and accelerating globally, they will require immediate action, strategic foresight, and a new set of competencies across all organizations and levels of government.

We believe at Resonance this will require designed innovation solutions, cross-sector partnerships, empowerment of often marginalized stakeholders, and implementation on the ground and in the field to deliver real, sustainable impact.