If you clicked on this published Insights with interest, there is a good chance that like many of us in the sustainability and climate space, you possess some understanding of “carbon offsetting” or “offsets,” and are less familiar with “carbon insetting.” Or maybe the former is still fuzzy.

Both are strategies or approaches that companies and organizations are exploring and adopting to address greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions as part of ambitious reduction goals and commitments. Both are also embedded in uncertainty (about science, about measurement, about scalability, about ultimate impacts), criticism, and potential untapped opportunity.

Despite the flurry of activity around carbon offsetting, there has been some cautionary advisement -- from governing bodies and activists concerned with potential greenwashing -- to forestry professionals and scientists who see the potential lockup of forests as part of carbon markets counter-productive in achieving goals long-term.

Much of this comes in the form of requested contemplation and assessment around one question. If carbon offsetting is intended to address the long-term goal of containing average warming below the 2°C limit, and thus requiring deep cuts in emissions from all sectors, does it really accomplish as a strategy what it sets out to do? The follow-up consideration is whether there is another, perhaps even better approach to achieving emissions reductions targets?

These queries underscore the purpose of this primer: to aid those of us in this space exploring offsetting (and insetting) initiatives on behalf of our organizations, clients, or partnerships in better understanding these schemas as both opportunities and challenges that require a deep-dive assessment before undertaking.

What is Carbon Offsetting?

Carbon offsetting has been around for a while. In terms of milestones and progression, the practice began in 1989 when Applied Energy Services, an American electric power company, offset its emissions by financing an agriforest in Guatemala. Three additional development phases spurred further expansion tied to corporate commitments to carbon neutrality and key policies. This includes the 1995 Kyoto Protocol, the 2005 EU Emissions Trading Scheme, and the 2015 Paris Agreement.

As researchers Becken and Mackey (2017) note, there are typically two different perspectives when it comes to carbon offsetting: the scientific perspective, and the policy perspective, with appreciated differences among the two.

The Scientific Perspective

Carbon offsetting from the scientific perspective examines the benefits and limitations of carbon offsetting schemes through the lens of the global carbon cycle and the major “stocks, flows, and natural processes which regulate, among other things, the atmospheric concentration of CO2,” (Becken and Mackey, 2017, p. 72).

More generally, carbon offsetting is any reduction of GHG emissions (carbon dioxide, methane, nitrous oxide, and various fluorinated gases, often conveniently lumped together as “carbon”) to make up for emissions that occur elsewhere.

At the organizational level, carbon offsetting is the action or process of compensating for GHG emissions arising from the organization’s industrial or other activity, by participating in external programs designed to make equivalent reductions of CO2 in the atmosphere through an array of activities and offset strategies in another place. Participation in offsetting presumes that a broader schema with multiple participants will help the collective “us” meet ambitious targets and reduce global annual carbon emissions by 50 percent by 2030, and net-zero by 2050, to prevent global temperatures from rising.

How is an offset accomplished from the science perspective?

Nearly 70 percent of carbon offsetting activities and approaches are considered “nature-based,” and you can recognize these because they typically (and often explicitly) include “conservation,” “restoration” or “management” activities that seek to avoid, reduce, or sequester GHG emissions. Such offset projects might include conserving and protecting landscapes to limit deforestation, for example, or restoring ecosystems such as drained peatlands so they can sequester (the scientific process of capturing and storing atmospheric CO2) carbon.

Participating in carbon offsetting requires a company or organization to first have an accurate understanding and measurement of its own emissions, or carbon footprint, across the organization and its supply chains.

How to Determine an Organization’s Carbon Footprint

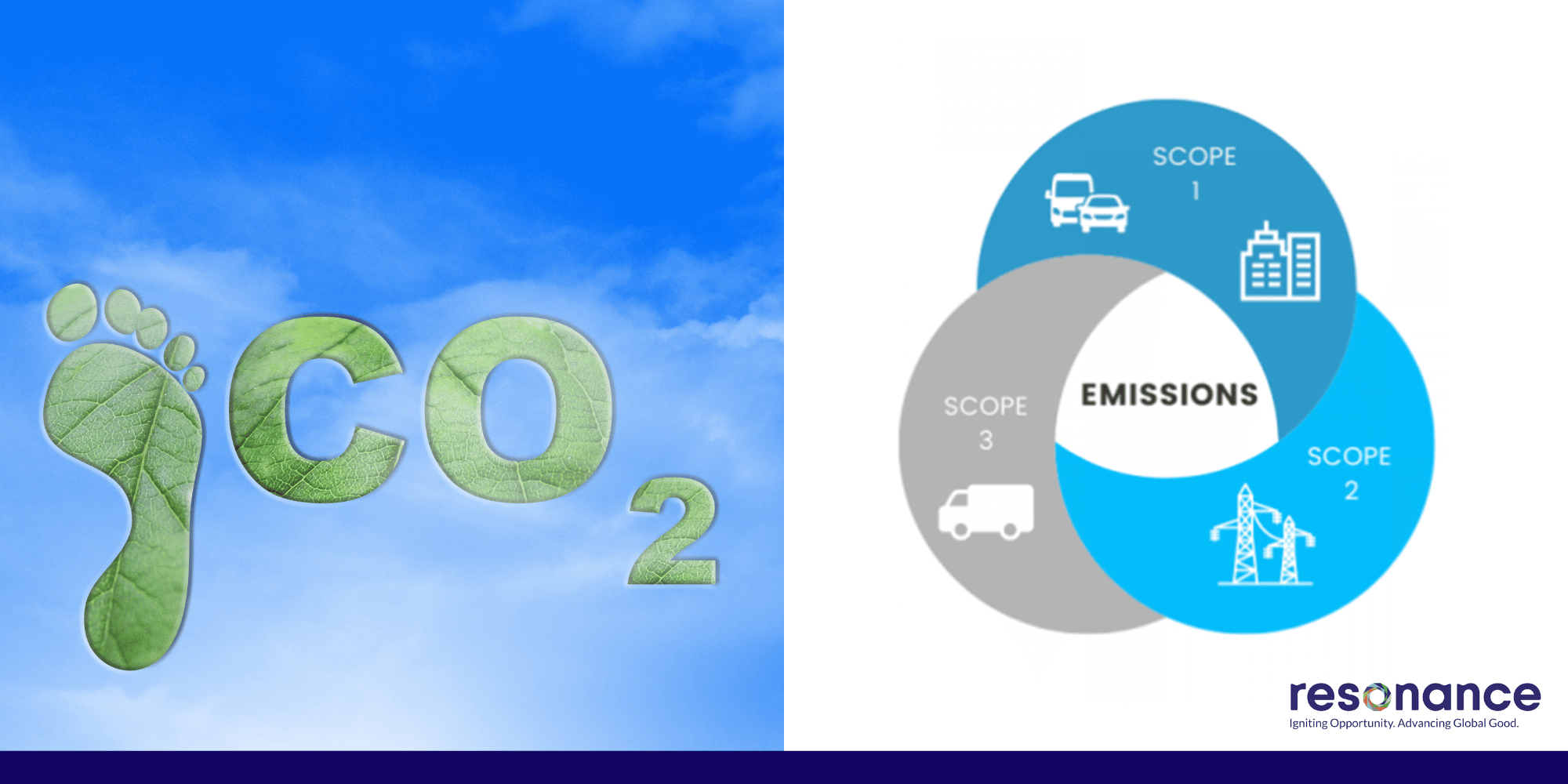

A carbon footprint is the total amount of CO2 and other GHGs the activities a person or organization generates. It includes both direct (originates from a source the reporting entity owns) and indirect (results from the entity’s activities but originates from sources the reporting entity doesn’t own) emissions. In the vocabulary of supply chain management, this refers to as upstream or downstream activities.

Companies must calculate and measure emissions.

Although no one claims it’s an easy lift, there are specific protocols to help companies calculate and measure emissions. This includes the GHG Protocol, an internationally recognized accounting standard that helps companies and organizations measure and manage GHG emissions. When we hear discussions around SCOPE, they are derived from the protocol, which divides emissions into three areas or scopes:

- Scope 1 is direct emissions from sources an organization owns or controls.

- Scope 2 is indirect emissions from electricity, heating and cooling resources, and steam, an organization buys, typically for production and operations.

- Scope 3 is other indirect emissions that come from an organization's value chain.

These emissions are expressed in tons of carbon dioxide equivalent and include other GHGs, and there are expectations that companies will regularly assess their carbon footprints and include them in sustainability, ESG, and other financial reports.

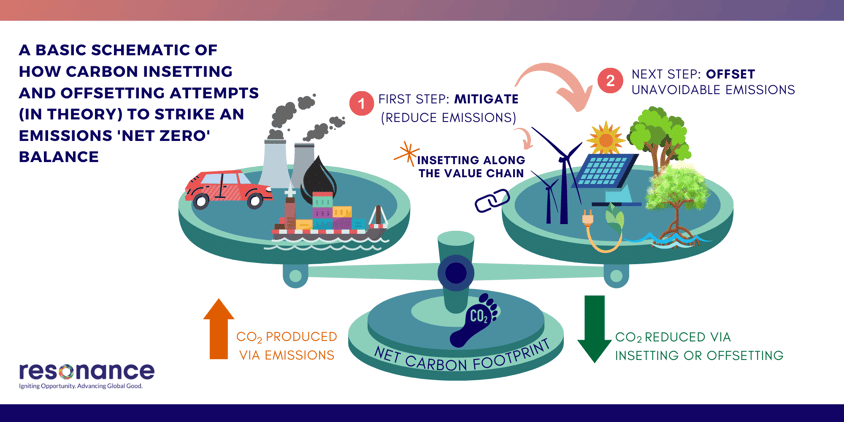

Primary Strategy: Reduce Emissions First

Once an organization measures its emissions and identifies the sources (determining and mapping its carbon footprint), it can develop a sustainability strategy. Guidelines for reducing emissions are detailed in the Science Based Target initiative (SBTi), which aligns with the goals of the Paris Agreement.

Energy use typically comprises about half of a company's carbon footprint. To reduce those emissions, the SBTi advises companies to use 80% renewable electricity by 2025. Carbon reductions can also be achieved in other ways, like contracting with rental car services that provide electric vehicles for employee travel, for example, or using sustainable and carbon neutral technology to produce goods.

Secondary Strategy: Offset Remaining Emissions

Emissions that cannot be reduced outright can be in our current policy schemas “offset.” This means organizations can purchase carbon ‘offsets’ or ‘credits’ to decrease their carbon footprint. Fundamental to the concept of a carbon offset is the notion of “additionality,” and you will hear this term used a lot in discussions of offsetting. Additionality differentiates the emissions reductions produced by an offset project from the “business-as-usual” (BAU) scenario of baseline emissions without the project.

For every metric ton of emissions that is reduced, a carbon credit worth one metric ton of reduced CO2 can be claimed, and, through a market-based scheme, the resulting carbon reductions can be sold as part of established markets as “carbon credits.” Essentially, when the number of carbon offset credits obtained is equal to an organization's residual emissions in their carbon footprint (representing emission removal or reduction that would not have happened otherwise), that organization is considered “carbon neutral.”

The Policy Perspective

The idea of “carbon offsets” has also developed meaning and usage because of negotiated climate change policy between and among national governments via governing bodies like the United Nations. And this context may have overlaps but is not always consistent with the scientific perspective.

There are two key international frameworks in use that employ different accounting conventions regarding offsetting. The United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) classification system seeks to provide consistent estimates of the changes in the release of net anthropogenic emissions into the atmosphere by a country over time and is used by all state parties in their annual national inventory report.

Succeeding the Kyoto Protocol, the Paris Agreement signed at COP21 in 2015 and effective in 2016 has as its goal to “hold” the increase in the “global average temperature to well below 2°C above pre-industrial levels” and pursue efforts “to limit the temperature increase to 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels.” Unlike Kyoto, which was a top-down approach to setting climate and emissions targets, the Paris Agreement is a bottom-up approach in which each country details the mitigation contributions it pledges to undertake to reduce its emissions.

Specifically, each ratifying party must submit and communicate a nationally determined contribution (NDC) describing both its mitigation contributions and climate actions. It also includes a commitment that these are ‘undertaken on the basis of equity, and in the context of sustainable development and efforts to eradicate poverty, which are critical development priorities for many developing countries’ (United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) Website).

Article 6 of the Paris Agreement establishes three approaches for Parties to voluntarily cooperate in achieving their emission reduction targets and adaptation aims set out in their national climate action plans under the Agreement (Nationally Determined Contributions, or NDCs). One of these approaches is through the Article 6.4 Mechanism, a mechanism “to contribute to the mitigation of greenhouse gas emissions and support sustainable development” (Paris Agreement, Article 6, paragraph 4).

With the inclusion of new rules (Decision 3/CMA.3), through this mechanism, a company in one country can reduce emissions in that country and have those reductions credited so that it can sell them to another company in another country. That second company may use them for complying with its own emission reduction obligations or to help it meet net-zero. In the context of the policy perspective, a carbon offset is defined as occurring when an individual, company, NGO, or state invests in a project elsewhere that results in a reduction of GHG emissions that would not have occurred in the absence of the project.

The Growing ‘Offsetting’ Market

It becomes clear in examining offsets through both the science and the policy perspective that “credits” can be incurred as part of offsets (science perspective) and traded (as part of a greater policy perspective). Here is where the two schemas intersect, overlap, and diverge, giving way to a growing ecosystem and “market” that includes an array of stakeholders and participants including companies, nonprofits, governments, partnerships, verifying agents, specialists, consultants, and investors, among others.

How might this play out in practicality? Let’s use two examples directly from the World Economic Forum’s article: Explainer: Carbon Insetting vs Offsetting.

EXAMPLE 1

In the first example, company A could offset its unavoidable emissions by purchasing carbon credits from company B that is in the business of, or uses, renewable energy. Company B in exchange would set up a new solar plant or a new wind farm. In this case, B benefits from clean energy and A from its reduced carbon footprint.

EXAMPLE 2

In another example of an offsetting exchange, company A could pay company C for carrying out reforestation initiatives. In this case, company A has once again offset its emissions in the environment, and in exchange, company C has helped protect biodiversity and create jobs for the indigenous communities that will look after the forests.

Article 6 of the Paris Agreement and Voluntary Carbon Markets

Carbon offsets are created under either formal schemes, established and regulated by governments and international bodies like the UN, or through voluntary offset markets.

In addition to establishing a climate goal of limiting the Earth's warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius, the Paris Agreement has further validated the role of offsets through established guidance for international trading between domestic carbon markets.

In fact, the rhetorical framing of Article 6 is explicit in encouraging multi-party cooperation and collaboration. It establishes cooperative approaches in the form of bottom-up bilateral or multilateral agreements (Article 6.2) and a centralized mechanism (Article 6.4) through which countries can agree to trade ‘emission reductions’ or ‘mitigation outcomes’ to meet their NDCs, as long as a robust accounting framework is applied (and communicated).

What has emerged then are two distinctively different carbon markets: compliance markets, in which regulated entities obtain and surrender emissions permits (also called allowances) or offsets as part of compliance with an imposed regulatory act or regulation. And, as we have introduced as part of discussions of the Paris Agreement and Article 6, the voluntary carbon market (VCM), in which carbon offsets are not purchased to be used as part of a regulated, compliance market, but rather with the “intent to re-sell or retire to meet carbon neutral or other environmental claims" (VCMI, 2021).

COP26, the Article 6 VCM Rulebook, and Clarifying Guidance

Among some of the most important outcomes of COP26 held in Glasgow in 2022 was an anticipated Article 6 rulebook, which issued clarifications around the frameworks and procedures of Article 6. Although this work is considered significant progress in providing clarity, there is still a great deal of uncertainty around the implications on VCMs.

The Oxford Institute for Energy Studies published a recent paper that addressed the context of this uncertainty across schemas and carbon markets broadly, and these are summarized here:

- There is tremendous uncertainty on what investors can claim by purchasing various types of carbon credits on the VCMs.

- There are tensions between the promotion of carbon markets to raise finance on the one hand, and supervising and regulating those markets to ensure environmental integrity and sustainable development goals and commitments on the other.

- There is tremendous concern regarding the proliferation of regulatory and supervisory initiatives, and the speed at which they are emerging, contributing to layers of uncertainty regarding which regulations will ultimately apply.

- There is a great deal of uncertainty over the nature of the offset carbon credits that will be available on the markets given what multiple bodies and stakeholders engaging in the external policy perspective are prioritizing as potential solution pathways. In other words, will they be nature-based solution credits (NbS); ‘avoidance’ carbon credits; emerging carbon dioxide (CDR) removal technologies; or some combination of the array of approaches?

We recommend those engaged in the prospect of offsetting on behalf of their organizations or clients read the full paper. To paraphrase from the authors in detailing how the article is structured, readers will gain a better understanding of not only Article 6 guidance and implications for carbon markets (in particular the specifics of the type of credits that can be originated, and rules applied), but also the implications for VCM and the extent to which different types of credits might emerge. The authors also address the role of corporations as drivers for demand for carbon credits to meet their net-zero claims, and conclude with an examination of potential sources of risks and mitigation practices and instruments that market participants in the VCM can adopt.

Criticisms of Carbon Offsetting

There are many broad criticisms of carbon offsetting and carbon offset markets put forth by experts and organizations across the spectrum and across geographies – from environmental advocacy groups to NGOs, as well as scientists and even businesses. Broad published critiques that include depth of treatment in terms of analysis should be explored before undertaking projects or investing in markets as the only focused solution or roadmap. We have provided the categorical criticisms here; generally they fall into the following:

- Carbon offsets do not effectively reduce climate change.

- There are not enough offsets for all our CO2 emissions.

- Carbon offsetting is a red herring in that it fools people into thinking the solution is adequate, preventing us from engaging in the kind of transformative change we need to reach established goals.

- Carbon offset projects have adverse impacts on local communities and may cause conflict or make other environmental problems worse.

- Emissions reductions often rely on vague predictions.

- There are significant risks to forests after a project ends, as carbon sequestered is likely to be released back into the atmosphere.

- Offset projects tie up forests that might be more beneficial in addressing other challenges or societal needs.

- Questionable “Additionality,” in that carbon offsetting projects may not be additional, meaning the project does not contribute to achieving additional climate benefits compared to if the project had not existed.

What is Carbon Insetting?

Carbon insetting refers to the financing of climate protection projects along a company’s own value chain that demonstrably reduce or sequester GHG emissions, and thereby achieves a positive impact on landscapes and ecosystems associated with the value chain, as well as local communities and stakeholders.

As described by the International Platform for Insetting, insetting is the implementation of nature-based solutions such as reforestation, agroforestry, renewable energy, and regenerative agriculture. The organization likens insetting as an approach to emissions reductions and meeting temperature goals as “doing more good rather than doing less bad.” For example, some insetting initiatives may improve the livelihoods of indigenous and local communities.

In the same way companies and organizations must examine their carbon footprints prior to embarking on carbon offsetting and carbon credit exchanges, organizations must also determine and map their own supply chain to identify and quantify where their GHG emissions are embedded before embarking on their insetting journey.

Typically, the most pronounced hotspot is often a company's source of energy, particularly for companies engaged in production and transport; thus, investing in renewable energy technologies such as wind or solar would be an effective first step solution.

A thorough mapping and analysis of a company’s carbon footprint upstream and downstream in its supply chain can also reveal other places and processes that are a locus for optimizing insetting.

For example, companies might consider planting trees on its suppliers’ unused farmland, or supporting suppliers in their transitions to regenerative agriculture practices. Many more holistic, nature-based solutions also have additional ecosystem services and benefits such as soil improvement, water conservation, absorbing greater carbon, and even providing new opportunities to diversify agricultural products.

Adopting Both Insetting and Offsetting May Prove More Effective at Goal-Attainment

Some of the most recent reports indicate the world is on track for a global temperature rise of 2.7°C by the end of the century. With less than a decade to halve our emissions, the pressure on the public and private sector to lower their GHG emissions is mounting.

As nations put forth a collective net zero mindset at the intersection of the science and policy perspective as a guide for companies in decarbonization efforts, it is clear that companies should mitigate first and then offset unavoidable emissions. What lies between these two measures, as we have explored, is carbon insetting.

There are numerous benefits associated with insets in that emissions are directly avoided, reduced, or sequestered within the company’s value chain. They are not sold as a credit in regulated or VCMs to offset another organization’s emissions by capturing carbon somewhere else. Carbon insetting also means investment in an array of tools, innovations, and sustainable practices that help prevent emissions from happening (mitigation) in the first place. And many of these are nature-based products, which may have the added benefits of ecosystem restoration, biodiversity protection, and natural resource conservation.

That's not to say offsetting activities should not be pursued. Certainly, there are numerous collaborations supported by policy bodies that are contributing to growing carbon markets.

However, given the complexity and uncertainty of offsetting activities, companies should attempt to make tangible progress in establishing and carrying out insetting activities as part of their goals and roadmaps, particularly as an immediate pursuit. It may be that adopting both insetting and offsetting will prove more effective at goal-attainment in the long-run. But much is still unclear.

To that end, and returning to our initial premise, it is imperative on those of us working in this space in representing organizations, companies, clients, and partnerships, to be vigilant in learning all we can about these frameworks and approaches as they grow, evolve, and transform the way we operate, from both the science and the policy perspectives, in an effort to deliver more meaningful change and impact.