Each month, Resonance is featuring Insights under the umbrella, ‘Research that Resonates,' introducing readers to recent and important academic research projects and findings that are important to our work, but often behind a paywall. To date, we have discussed articles focused on microplastics, including the latest research on microplastics detected in breastmilk.

Much in the same way the work of science journalists makes scholarly research more accessible, we share the same goal with this series.

This month we report on an inexpensive and simple approach to destroying harmful “forever chemicals” that are persuasive in the environment.

A team of international researchers, led by scientists at Northwestern University, have found a promising way to reduce this global threat to human health, the environment, and biodiversity, by breaking down these pernicious chemicals and rendering them harmless.

What Are Forever Chemicals?

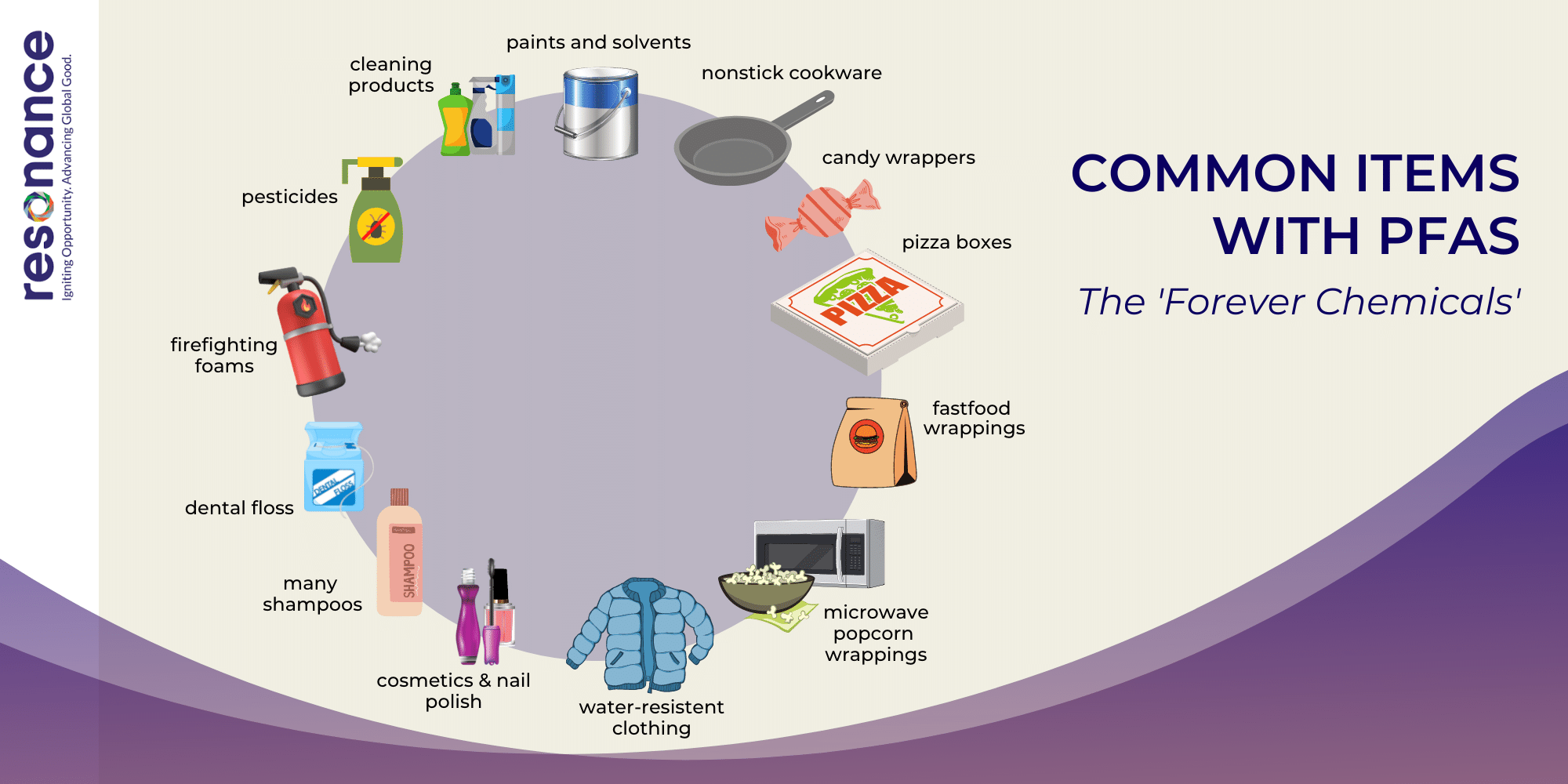

PFAS (per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances) are a group of some 4,500 synthetic chemicals used to make products and coatings that resist heat, oil, stains, and water.

First introduced into manufacturing in the United States in the 1940s, these chemicals were used worldwide to create everyday products -- from waterproof clothing and stain-resistant carpeting to nonstick cookware, food packaging and personal care items like shampoo and mascara.

Today, because of their widespread use, PFAS are everywhere in the environment.

PFAS are found in coastal waters and in rivers and lakes throughout the world. They have been detected in livestock, birds and fish as well as in seafood and cow’s milk. They are found in the water we drink and the air we breathe – even in our bloodstreams and our breast milk.

The molecular structure of PFAS includes a carbon chain strongly bonded to atoms of fluorine. The strength of this carbon-fluorine bond makes PFAS extremely difficult to break down. Some types of PFAS can take over 1000 years to degrade, which is why these “everywhere” chemicals are also known as “forever” chemicals.

Research studies over the years have linked high PFAS exposure to serious health problems including several types of cancer, disrupted hormone production, birth defects, and kidney and liver damage.

The varying concentration of PFAS found throughout our global water supply and agri-food supply chains is cause for serious concern.

Breaking The Unbreakable Bond

New research suggests that these forever chemicals may not be forever after all.

In a recent study published in Science, the research team reported they successfully destroyed PFAS molecules under low temperatures by mixing them with two inexpensive, relatively harmless compounds: sodium hydroxide (lye), which is used to manufacture soap, and dimethyl sulfoxide, an FDA-approved chemical used in medication to treat bladder pain syndrome and in products that relieve joint inflammation.

Working with two major classes of PFAS, the researchers used low temperatures (~100 C) to heat the chemicals in the two reagents and target the cluster of carbon and oxygen atoms at the head of the carbon-fluorine chain. Within 24 hours, the oxygen atoms began to break down, causing a chain of reactions that left behind nothing but benign chemical waste.

The unbreakable carbon-fluoride bond was broken.

The Challenges Of Safe Disposal

This approach helps remove a major stumbling block in PFAS remediation: the problem of safe disposal.

Carbon filtration, ion exchange, and reverse osmosis are the most effective techniques used today to separate PFAS chemicals from water and soil. But finding methods to safely dispose of these toxic compounds has proved more difficult.

Typically, PFAS have been disposed of in landfills or destroyed through incineration, a harsh process which uses high pressures and extreme temperatures (above 1,000°C) to break down the chemicals. But there is evidence that the current disposal methods may in fact lead to the further spread of these contaminants into the environment.

For example, soil and groundwater near a New York incineration site that was destroying firefighting foams manufactured with PFAS chemicals, tested high for PFAS levels. The contaminants were likely spread through airborne particles released during the burning process. Burying the toxic compounds, which will eventually leach into the soil and groundwater, only extends the problem farther into the future.

Although the researchers have acknowledged that more work is needed to move the technology from the lab to the field, their innovative process opens up new possibilities for eradicating these forever chemicals from the environment.

Why This Research Resonates

This study, which was supported by additional research and chemical modeling developed by researchers at Tianjin University, The Chinese Academy of Sciences, and UCLA, is an example of the power of international scientific collaboration to find solutions to the most pressing issues of our time.

Today, our global response to the PFAS contamination crisis includes partnerships among government and nongovernment agencies, the scientific and medical communities, and public health sectors.

Together, they are working to establish safe PFAS guidelines for drinking water, to identify new and emerging contaminants, and to further understand the process of PFAS bioaccumulation, and its adverse effects on human and animal health.

In the United States and in many parts of the world, industry has voluntarily stopped using some PFAS chemicals, including Perfluorooctanoic Acid (PFOA) and Perfluorooctane Sulfonate (PFOS), two of the most common and toxic forever chemicals used in manufacturing.

And although considered less toxic, newer forms of PFAS continue to be introduced. Last year, the EPA released a three-year plan, the PFAS Roadmap, which outlines policies and guidelines to protect public health and the environment and hold polluters accountable.

Forever chemicals are an urgent public health and environmental threat for communities across the globe. Partnerships and initiatives facilitated and funded by catalyst organizations, will be the first and perhaps best step to finding solutions.