The American Farmland Trust (AFT), established in 1980 with a threefold mission to protect agricultural land, promote environmentally sound farming practices, and keep farmers on the land, held a livestream event on March 9, 2023, called “Healing Grounds: Regenerative Agriculture and Justice,” inspired by a book written by author and professor Dr. Liz Carlisle with a similar title.

This AFT ‘Free Range’ conversation was facilitated by Gabrielle Roesch-McNally, the organization’s Women for the Land Director, who said she was inspired by Carlisle’s book, Healing Grounds: Climate, Justice, and the Deep Roots of Regenerative Farming, and the work and narratives of the women farmers included. Three themes emerged from this livestream conversation:

- The value of deep land connections;

- The reemergence of needed deeply rooted intersectional, regenerative practices; and

- The questions of how do address ‘Land Justice;’ what does it mean, and how do we get there?

Carlisle’s work, and book, focuses on examining relationships between organic and regenerative farmers to the land, many indigenous, and the ways in which traditional farming and regenerative practices, despite working through entanglements with complex colonial histories, hold promise in addressing wicked challenges like climate change.

We highlight here the background of each of the participants through the lens of their expressed land connection and include some (brief) key takeaways.

We encourage those of you who are interested in this topic to watch/listen to this now recorded conversation, linked again, here, to gain deeper insights shared in as part of this valued conversation.

‘Deep Land’ Connections and Regenerative Ethos

When asked to describe the inspiration for her book, Carlisle said she was always drawn to her grandmother’s deep connection to her family farm, lost in the historic Dust Bowl, and the wisdom she had relayed over the years regarding what contributed to that loss that in hindsight. This includes her grandmother’s conveyance of her father’s adoption of ill-advised government practices to over-plow, which set their farm up for catastrophe.

It was Carlisle’s desire to better understand the ways in which her grandmother’s deep ‘land connection,’ and associated wisdom, might inform her own, including a better understanding of the ways over-extractive rather than restorative, regenerative practices, have played a major role in current land conditions. She also wondered about other women farmers and their connections to the land, and that has been the central question that has guided her work and the narrative profiles in her book.

Nikiko Masumoto’s Multi-Generational Farm and Japanese Roots

The livestream conversation also included panelist Nikiko Masumoto, a featured farmer in Carlisle’s book. Masumoto is a fourth-generation farmer, artist, ‘memory keeper,’ and cultural organizer, who with her family cultivates certified organic peaches, nectarines, apricots, and grapes (for raisins) on their 80-acre Masumoto Family Farm south of Fresno, California.

Masumoto grounded the discussion of her narrative of land and landscape connection to the physical context of her family’s farm (an amazing storyteller!): dry, tan, sandy-loam soil in the mega-drought period in California, rendered darker chocolate brown with recent intermittent storms. The land is fed by the waters of the King’s River, and these waters used to feed the largest freshwater lake west of the Mississippi, the Tulare Lake, once home to the Yokuts, which in its disappearance post-dam construction, relays the ways in which land and farming is indeed entwined in the complex histories of colonialism.

Her family’s story of “claiming a place to belong,” begins with the narrative of her grandparents who were each with their respective families, part of the forced evacuation of 120,000 West Coast Japanese Americans in 1942 due to the wartime hysteria. Her grandmother’s (Sugimoto) family was relocated to the deserts of Arizona, imprisoned at Gila River Canal camp, Block 22. They spent 4 years behind barbed wire, coping and enduring while trying to make the most of the moment. Not long after their release, her grandparents married, and gambled on purchasing a 40-acre farm filled with vines, tree fruit and tons of hard pan, considered by most “unfarmable.” They managed to create “through love” notes Masumoto “a farm and farm family, deeply connected to the land.”

“We do our best to sustainably farm our 80 acres south of Fresno and share our harvests through food, writing, and art,” she says of her family who are creators, artists, storytellers and writers.

Latrice Tatsey’s Connections to Ancestral Land and the Importance of Sacrifice

Also featured as part of the conversation (and in Carlisle’s book) was panelist Latrice Tatsey, a soil scientist, cultural science lead, and interim supervisor for the regenerative grazing initiative at the Piikani Lodge Health Institute on the Black Feet Nation. As a registered member of the Amskapiipkini (Blackfeet) Nation, her connection to land has been forged working the land of her indigenous ancestry along the Rocky Mountain front, or what she calls the “backbone to Mother Earth, (“our Mother”).

She describes much of her connection as one through multi-generational sacrifice – sacrifice when her people were facing starvation, or when Buffalo was taken away and they were forced to become more agrarian, or when closer to her own experience, her father and grandparents had to go “without,” once selling nearly their entire herd of cattle to make ends meet and keep their land, save for four small calves.

In many ways, those calves are reminder to Tatsey of rich, cultural relationships that tie generations together on her people’s land. Those calves are what kept her family and ranch going today. Knowing the sacrifices that underpin cultural relationships and understandings alive, such as Teepee rings, and buffalo jumps, gave her a deep-rooted cultural attachment to the land, as well as an agrarian attachment.

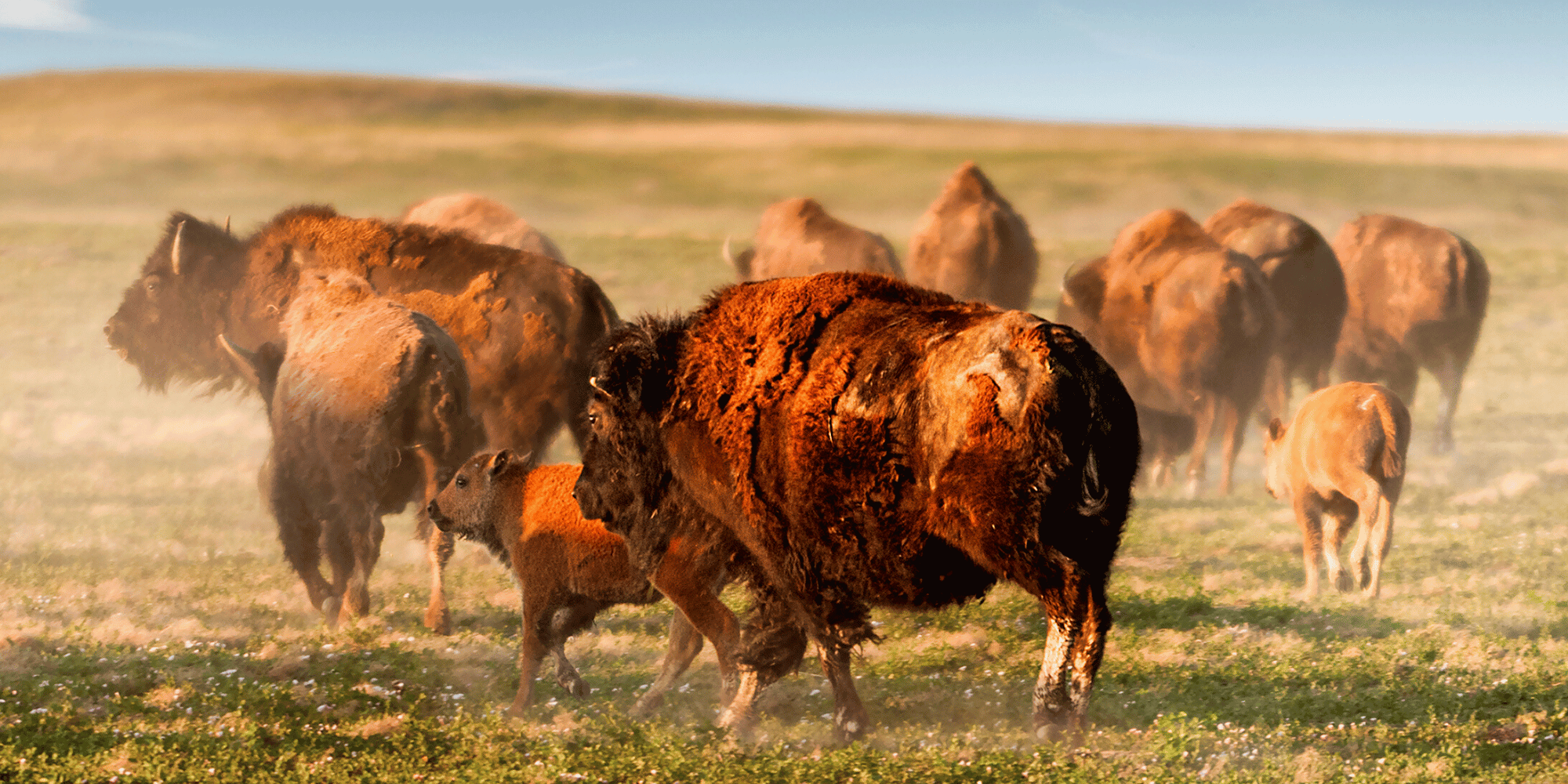

Today Tatsey is part of a broader effort to restore bison to the landscape, talked about no longer in just the past, but full circle to see them on the land today, and the sacrifices she sees today will be made, she notes, to say, “we won’t leave our land,” determined she can raise her children there.

Connections of Climate Change to Agriculture through Regenerative Practices

Carlisle said her book project began with questions about soil and climate in light of the differing opinions across the scientific and practitioner community, and the extent to which regenerative practices might or might not play a significant role. What she discovered was that much of the information converged around the notion of deep “roots,” related to soil, and the critical relationships between plants and microbes.

“Many of the regenerative ag techniques have “deep roots” in indigenous communities and communities of color - practices that precede many of the current discussions we are having today,” noted Carlisle.

The practice and metaphor of deep roots centered participants in a dynamic conversation about many of the practices that rose through the generations of their families (layered knowledge system) that many who are engaged in Western agriculture today might dub as new, or emerging, under the umbrella of “regenerative.”

This includes practices that might lead to greater carbon sequestration (keeping roots in the ground as part of perennial practices) , and practices that promote nutrient cycling that have rich histories over thousands of years in Asian farming systems such as use of cover crops and living mulches, and composting, It also includes indigenous approaches to regenerative grazing that mimicking the Bison as a teacher, including the use of fire as a tool, to maintain abundance and diversity in grasslands. It includes, too, agroforestry practices seen throughout the African diaspora that are being considered today.

The rooting metaphor also points to the reality of deep histories of purposeful uprooting of people and the need, notes Carlisle, to confront and address these colonial histories and legacies if we are going to address the real challenges of climate change through agriculture.

Land Justice: How do we Get There?

When asked to further describe how they view their own engagement in multi-generational and intersectional regenerative practices alongside “land justice,” both Tatsey and Masumoto were metaphoric, too.

Tatsey: a Focus on Relationships

Tatsey notes we have a responsibility to care for the land, and that responsibility is part of deep relationships.

“When you look at things through relationships, you think about the need for both reciprocity and nature in the balance, in the lessons and integrity in our teachings, there is no hierarchy; we are not above or below animals. We are all beings living on this land, and we had a role. For me, it’s taking that relationship back and applying it to what our people have told us, and finding ways to incorporate it into the practices we are using today. In terms of justice, I recognize my people don’t have the same access or opportunity to garner the resources necessary to take these practices as caretakers of the lands for the generations after us, just as those who came before us made decisions for which we are the benefactors. It is caretaking – the responsibility of taking care of Mother Earth.”

Masumoto: Through “Loving” and Connection to 'the Blooms'

Building on what Tatsey described, Masumoto noted that despite our sense of urgency, and our Western propensity to address challenges like climate change in a linear fashion, or checklist, our orientation in regenerative approaches should be relational ways of existence – an orientation to life in circularity and reciprocity: between beings; between plants and beings; and between people – it never ends.

“Regenerative agriculture means to me – what are the questions and what are the practices that we want to live with forever?...And with that, I think a lot about relationships of love and land. Relationships are not just about sweetness, but also vulnerability, accepting our flaws, and working through tough times. And I desperately want more people to fall in love with land in a healthy way; that is not necessarily one of ownership, but even just about coming to see the blossoms. Bloom happens once a year. So, what are the things we can do to adjust in our life to live in the cycles of nature that invite us into deeper relationships with nature? Let’s do it. Reciprocal relationships. Bathe in the blossoms.”

Land Justice Efforts and Resources

There was far more to this discussion before landing at the question of "how do we get to land justice?" (the last chapter of Carlisle’s book). Here the participants discussed some of the organizations and tools related to the challenges of land (and justice) and creative ways to think about land.

In addition to several indigenous groups working toward sovereignty and land reclamation, Carlisle mentioned both the NE Farmers of Color Land Trust and the work they are doing in this space, as well as a US Interior Secretary Deb Haaland's recent announcement as part of the Biden Administration’s Inflation Reduction Act for Bison restoration, among others. Tatsey noted the concerned efforts among indigenous groups to garner the resources they needed to both retain and reclaim lands that were part of the Blackfeet nation for centuries. The suggestion was there is great creativity in approaches and tools to address the entangled histories of colonialism that may, without focused effort, be barriers to widespread regenerative practice.

Regenerative agricultural practices and regenerative farm research is a major focus of interest among many of our clients, especially those in the food and beverage sector, as well as many of our cross-sector partnership initiatives. If you are interested in exploring partnership opportunities in agriculture and food security, we invite you to connect.

And to learn more about the work of the American Farmland Trust, and to listen and watch more of their "Free Range Conversations," visit the organization's website.