How Companies, Foundations, NGOs, and Governments Can Partner to Solve Business and Global Development Challenges

As companies grow, they must navigate increasingly complex social, environmental, and supply chain challenges that they can’t solve alone. Meanwhile, governments and donors increasingly rely on market forces, private sector innovation, and the economic opportunity created by companies to improve people’s lives. The success of each sector is inextricably intertwined.

Climate change, poverty, and inequity are among the most critical issues of our time. Cross-sector collaboration leverages the strengths of companies, governments, and donors to accelerate progress on these and other complex issues in a way that benefits everyone.

No problem! Just type in your email address below so we can send it to you.

Resonance Global needs your information to send you the content you’re requesting. We may contact you in the future about related resources. You can unsubscribe at any time. For more information visit our Privacy Policy.

Cross-sector collaboration is when two or more organizations work together across sectors – industry, nonprofit, and government – to achieve mutually beneficial outcomes. Successful collaboration may lead to the formation of a cross-sector partnership, in which partners formally agree to leverage their resources and funding to work toward shared, measurable goals.

A well-designed and effective cross-sector partnership benefits partners through:

As the world becomes more complex, it’s never been more critical for organizations to work across sectors to achieve shared goals. That’s why Resonance’s founder Steve Schmida created this guide to help demystify cross-sector collaboration. With decades of experience bringing companies, nonprofits, and government organizations together, Steve has literally written the book on partnering with purpose. Below, we share some highlights that help illuminate the ways stakeholders can work together to achieve outsized impact.

All organizations share one thing in common: some problems are simply too big to solve alone. But that doesn’t mean partnership is always the best solution. When considering a cross-sector partnership, there are three key questions to answer:

Before you can determine whether a partnership is the right tool, be sure you are clear on the problem to be solved.

You can compare simple problems to baking a cake: although it might not be easy, you can replicate the results consistently by following a tried and true recipe.

Complicated problems are more akin to sending a person into space. After years of experimentation and casualties, we can now travel beyond the atmosphere in relative safety – though certainly not cheaply or risk-free – by following a set of complex technical and managerial protocols.

Complex or wicked problems are another story altogether. There is no set process that you can use to solve them because they are intertwined with social, economic, and environmental issues that are always changing. Wicked problems are never entirely resolved, but organizations and countries may make significant progress through focused effort and collaboration.

Because partnerships are time-consuming to build and manage, they are generally most practical and effective when applied to complicated or wicked problems that no single organization can address on its own.

It may sound obvious, but partnerships depend on partners that share a common problem. Companies, governments, foundations, and civil society organizations might have different reasons for wanting to solve a complicated or wicked problem. Still, they must align on the nature of the problem – and each must be motivated to solve it.

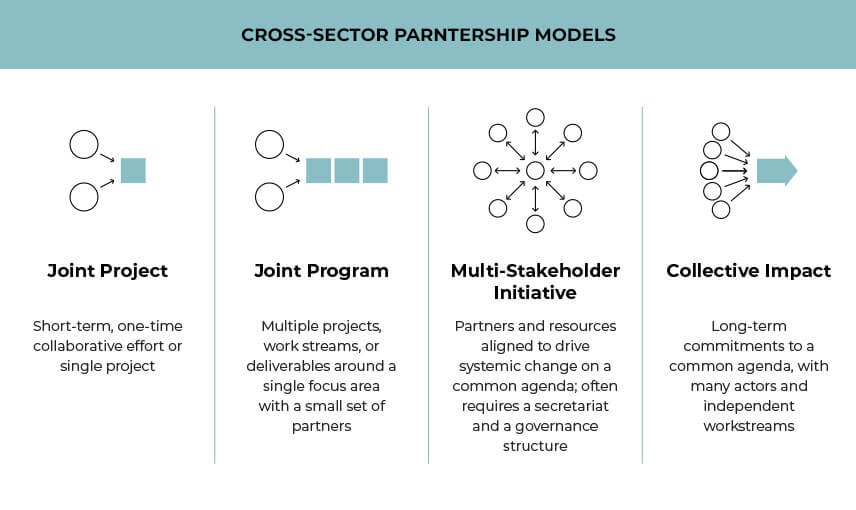

Joint projects tackle complicated problems that are isolated to a specific place and occur over a short period. Because projects often involve just one company and a nonprofit or government partner, the partnership's governance and management are relatively straightforward. The downside is that joint projects are usually transactional: they don’t represent deep, genuinely collaborative relationships. And if a partner drops out, the partnership will crumble.

The TV White Space Partnership was a joint project between Microsoft, the Government of the Philippines, and the US Agency for International Development (USAID), facilitated by Resonance, to extend internet access to remote and underserved coastal communities in the Philippines.

Joint programs are similar to joint projects, but typically involve several partners and workstreams over a longer timeline. In this model, partners work together to define a specific goal and coordinate a series of projects designed to achieve the goal within a few years. While individual partners may sign on or drop off as they complete workstreams, a joint program's success relies heavily on one committed partner to champion and coordinate various efforts.

The Last Mile Initiative was a joint program partnership between USAID and Qualcomm, Dialog Telecom, and the National Development Bank of Sri Lanka to extend internet connectivity and services to rural consumers.

In a multi-stakeholder initiative, numerous partners from across sectors work toward one or more clear solutions to a complicated or wicked problem. Generally, these initiatives involve several funders and a secretariat to coordinate implementation efforts.

The Global Alliance for Vaccines and Immunizations (GAVI) works with civil society organizations, manufacturers, governments, donors, companies, and more to help vaccinate almost half the world’s children against deadly and debilitating infectious diseases.

Collective impact initiatives address complex or wicked problems and involve a large number of loosely affiliated partners working toward system-level change. While each partner may work independently, they coordinate efforts and pool interests, resources, and capabilities to amplify impact.

The Platform for Accelerating the Circular Economy (PACE) works with global leaders and their organizations to accelerate the transition to a circular economy.

Before you identify your cross-sector partner(s), you need to confirm your problem. For instance, a medical company seeking to address heart failure in Ghana may find that the real problem is late diagnosis of hypertension, lack of awareness, and neglect of care plans. Uncovering the root problem(s) increases your chances of success, and helps you identify the partners that are best suited to help.

After engaging potential partners (see below), you may need to further refine your problem. That’s often a good sign – the process should be iterative and collaborative.

A landscape analysis can help you explore relevant value chains for potential partners. Create a map of all the organizations that are working on or affected by your problem. Remember to also consider those industries – such as technology and media – that might not be directly tied to the challenge but may still inform solution development. Below is a list of common partner types, and the benefits and drawbacks to working with them.

After identifying high-potential partners, it's time to engage. You may need to do some legwork to find the right contact at each organization.

Keep in mind that these first sessions are exploratory. Ask open-ended questions and listen more than you speak. Go into conversations with a clear idea of the root problem you are trying to solve, but expect to clarify your goals in response to the feedback you receive. Your sense of how to partner and what the partnership can achieve will evolve throughout the collaboration.

At this stage, you understand the problem, and you’ve spoken to a range of organizations and potential partners that either share your challenge or could possibly help shape a solution.

You seek motivated, committed partners who bring something critical to the table. In prioritizing organizations for partnership, consider:

This is where you need to get creative. You need to connect the dots to consider what you and your partners might do together to solve your shared problem or unlock new opportunity. Partnership ideation is more art than science, but consider the following as you work to sketch your partnership outline:

Download a free copy of Resonance’s Partnership Bluebook Template to evaluate cross-sector partnership concepts according to their potential for success.

Note that, at this stage, you are outlining your partnership model or concept. You do not – yet – need to be consumed by the details of specifying granular activities and timelines or pushing for firm and specific resource commitments from partners. Your partnership outline is the basis for the negotiations in the next phase (see Closing the Deal). You will refine and complicate this outline further as you move forward with negotiating, co-creating, and engaging with your partners.

Download a free copy of Resonance’s Partnership Concept Template, which summarizes the main features of the partnership and helps you develop a shared vision of success.

The Valley of Death is a term that venture capitalists use to describe the risky time period between a company’s startup and its revenue generation. A cross-sector partnership faces similar risk between the time partners first engage and eventually sign a formal partnership agreement. This can take six months or more, and it often spells death for promising partnerships.

Partners are more likely to cross this valley successfully by addressing the following:

Negotiating the partnership terms is less about aggressively pushing for something that will benefit your organization, and more about finding solutions that maximize success for all partners. Collaboration is all about building long-term relationships and ensuring that everyone wins.

Remember: Partnerships live or die by the commitment of all partners – you need to negotiate a partnership that motivates and fits each keystone partner. Some key tools to employ are active listening, ensuring a fair process, restraint, curiosity, respect for differences, and cultural awareness.

It’s important to understand the realities each partner faces as you negotiate and structure your partnership. Donors agencies and other tax-payer-funded organizations may prioritize process and program targets while companies often frame progress in terms of quarterly earnings objectives.

A partner may be blinded by commitment to a specific purpose or vision that keeps them from considering the related issues that must be addressed first. Seek to understand a partner’s incentives and constraints while articulating your own, to ensure that your partnership can balance needs and maximize progress toward shared goals.

To keep stakeholders engaged, you’ll need to clearly define the benefits each partner can expect to receive as a result of the collaboration. A company should establish the business case for partnership, which might include access to new markets or customers, increased productivity or operating efficiency, or sourcing more, better, or less-costly materials. For example, “Through the partnership, we will reduce our input costs by 10 percent over the next year.”

Though the business world historically cited profit as its central goal, many companies have also begun to declare a purpose, similar to a mission, that goes beyond mere profit (PepsiCo, Unilever, and Cargill are all good examples). If you work for a company that hasn’t defined a purpose, you may be able to review recent presentations, speeches, or interviews with leadership for clues on how to align your partnership with the values that give larger meaning to company strategy and operations.

Development or humanitarian organizations should document how the partnership will advance progress toward one or more of the sustainable development goals or toward a specific issue in a high-need area, such as creating access to clean water in Tanzania. Governments may express a desire to create jobs or improve livelihoods within a particular region or sector of the economy.

Before the formal agreement, you need a solid commitment from fellow partners. One strategy is to negotiate with them individually first – sometimes over the course of several meetings – to learn what they hope to achieve through collaboration (and how much they are willing and able to give). Another is to convene a roundtable where you’ve laid the groundwork in advance with one or more partners to encourage others to commit or step back.

Finally, it doesn’t hurt to create a sense of urgency by setting a deadline for commitments, for example in the lead-up to a global event or industry announcement.

It might seem counter-intuitive, but one of the top reasons that cross-sector partnerships fail is that partners haven't gained buy-in from their coworkers to ensure their organization can deliver on its promises. Coworkers and internal leaders may be hesitant to work with other entities with different goals, cultures, and hierarchies. And the fewer champions each partnership has, the higher the likelihood that staff turnover will collapse the entire partnership.

To ensure successful collaboration, each partner can gain internal alignment in the following ways:

As you are negotiating, partners should consider how the partnership will be governed. How and who will make decisions? Will all partners have equal say? Are there critical outside stakeholders who must be consulted? Generally, the simpler and more streamlined the system, the more quickly the partnership will be able to make forward movement.

One common model is to create a governing body comprised of one representative from each organization, that meets regularly to make decisions and review progress. Another is to create an executive group of highly committed partners that make most of the decisions, as well as a larger committee that keeps everyone informed and on track.

A partnership must be managed closely to ensure that activities happen on time and as planned. Manager(s) will also oversee the organization of governance meetings and creation of reports, external communications, and other important documents. Cross-sector partnerships often employ a partner for this role, appoint a third-party manager, or hire a dedicated partnership coordinator.

Whatever the form of your final cross-sector partnership, we advocate that you outline partnership terms, roles, activities, and parameters in a signed partnership agreement. Generally, these partnership agreements are not legally binding contracts; instead, they act to formally and transparently outline the expectations and aspirations of the collective partners.

In a partnership agreement, you’ll likely want to cover the following:

The launch of a partnership is full of excitement, as well as uncertainty. As partners move from thought to action, these tried-and-true attributes can go a long way toward ensuring success:

Once a cross-sector partnership has achieved its goals, partners should discuss whether and how to sustain the impact they have created. Could their solution create a business opportunity for one of the partners or stakeholders? Is anyone willing to pay for ongoing costs? What incentives might encourage or reinforce the change over time?

Partners may also want to consider whether it’s feasible to scale their results. If the collaboration is generating business value as well as positive impact in a particular market, you may want to enhance product or service offerings within that market. Alternatively, you may be able to offer the product or service across a wider range of market segments or geographies.

You’ll also want to consider these three factors:

If your partnership meets these criteria, discuss which model you’ll use to scale. Common options include a private, market-based pathway that leverages internal or external investment; a public-sector-led pathway developed in collaboration with host government(s); or a private-public hybrid that takes advantage of the strengths of both the market and the public sector.

For more information on how companies can partner with different types of organizations to reach business and sustainability goals, check out the book Kirkus Reviews calls “authoritative, all-encompassing, and richly detailed; a highly valuable partnership playbook.”

Steve Schmida’s Partner with Purpose: Solving 21st Century Business Problems Through Cross-Sector Collaboration is now available.

Some international donor organizations have set up platforms to make cross-sector partnerships quicker and easier. Below are a few notable examples:

For more free tools and resources, check out our list of online resources for building partnerships.

Whether you’re just starting to explore partnership strategy or you’re deep into implementation, if you have a partnership question, we’re here to help

Laurie Pickard is an expert in private sector engagement with 15 years of experience and a proven track record of facilitating market-driven partnerships. Her role also includes sharing partnership learning and supporting partners to apply Resonance’s suite of partnership development tools and methodologies. She brings experience in the international development sector, with a focus on inclusive growth, sustainable supply chains, and market systems development.

She has brokered multi-stakeholder partnerships with companies and development partners and has supported USAID Missions to build PSE technical and leadership skills. Laurie previously served as PSE Advisor and Rural Enterprise Development and Entrepreneurship Specialist at USAID/Rwanda.

Reach out to Laurie to learn more about how we can help you solve big problems through partnership.

© 2025 Resonance Global

Privacy Policy